Weapons and an armored vehicle at a MIMUSMA outpost in northern Mali. (Photo: MINUSMA/Harandane Dicko)

Within a single week in February 2021, militants from the Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA) overran Nigerian military bases in the towns of Marte and Dikwa in Borno State. More than 20 soldiers were killed in the attacks. The militants likely seized at least half a dozen vehicles and hundreds of weapons. The incidents were significant but unexceptional.

“Nonstate armed groups have regularly targeted and overrun peacekeepers and national armed forces to seize lethal and nonlethal materiel.”

Contingent-owned equipment (COE) loss has become a critical vulnerability for national armies and peace operations in Africa. Nonstate armed groups have regularly targeted and overrun peacekeepers and national armed forces to seize lethal and nonlethal materiel. This materiel represents a significant source of armaments for Africa’s militant groups, fueling instability on the continent.

As part of its “Silencing the Guns” initiative (now extended through 2030), the African Union Commission acknowledged COE loss from peace operations as a significant problem in a joint study with the Small Arms Survey. The primary sources of illicit weapons in Africa, according to the study, include national stockpiles and peacekeeping forces. These weapons diversions are largely due to battlefield loss, mismanagement, theft, and corruption.

This directly contributes to the capacity of violent extremist groups. Al Shabaab has secured significant lethal materiel from attacks on the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), as have the Macina Liberation Front (FLM) and other armed groups from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) and the Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel (FC-G5S).

Weapons and ammunition collected from armed groups in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

(Photo: MONUSCO/Sylvain Liechti)

COE loss has occurred in at least 20 peace operations in 18 African countries. Lethal materiel lost in the past 10 years alone has included many millions of rounds of ammunition, thousands of small arms and light weapons, and likely hundreds of heavy weapons systems. Nonlethal materiel, such as unarmed vehicles and motorcycles, uniforms, communications equipment, and fuel, have also consistently been a target. Armed groups use this materiel against peacekeepers and armed forces in complex ambushes perpetuating the cycle of munitions loss.

For widely differing reasons the European Union (EU), China, and Russia appear set to increase their supply of lethal materiel to African governments. Unless COE control measures are strengthened, these arms flows could contribute to greater instability.

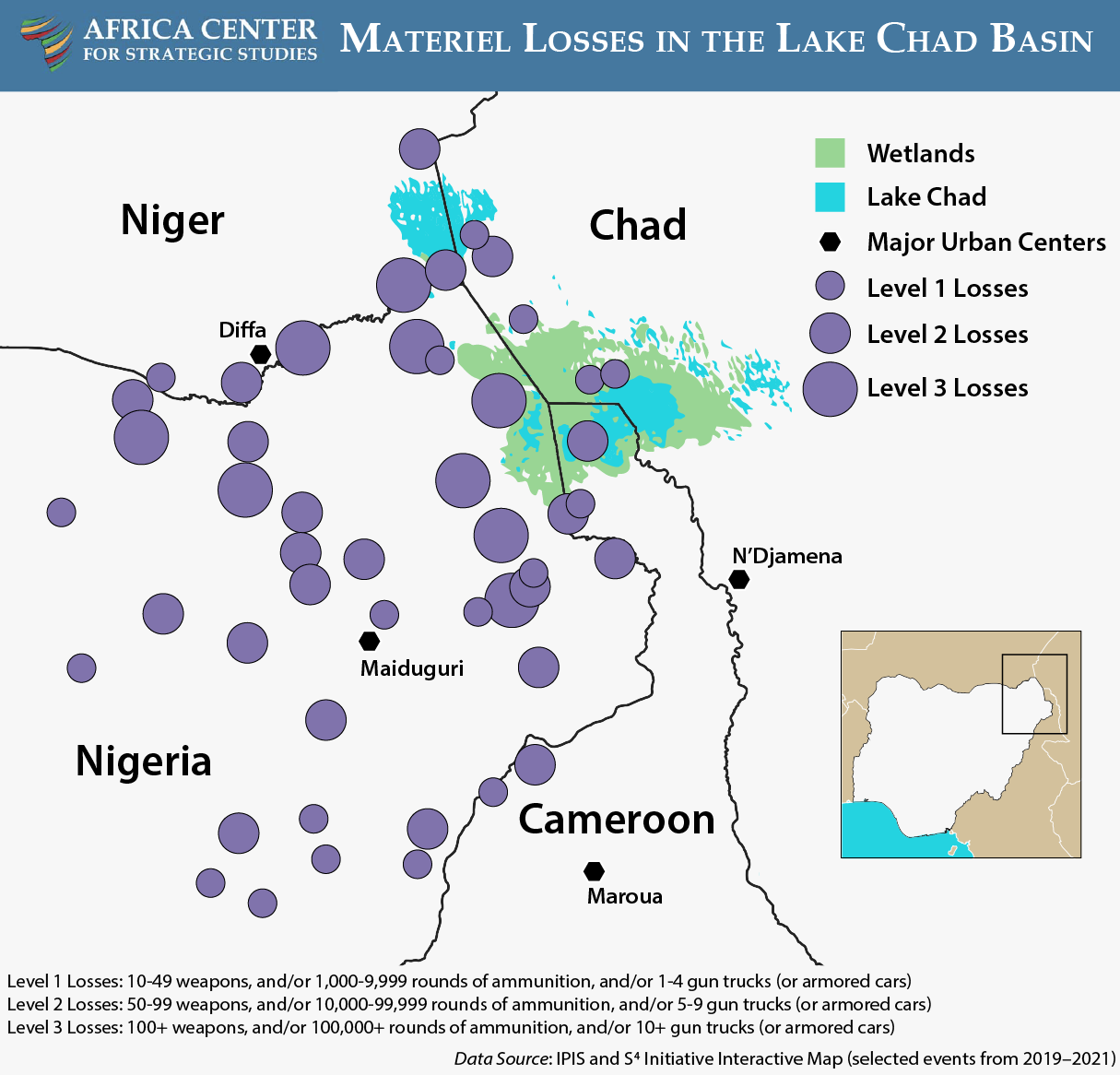

Lethal Materiel Loss in the Lake Chad Basin

Attacks on security forces by Boko Haram and ISWA in the Lake Chad Basin underscore the seriousness of this challenge. These groups have sustained their insurgencies for years utilizing massive amounts of COE seized from the armed forces of Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Military bases across the Lake Chad Basin have been attacked and looted. Boko Haram and ISWA have also secured lethal materiel from security forces in transit during attacks against patrols, convoys (both of supplies and troop movements), and during escort duties.

The Safeguarding Security Sector Stockpiles (S4) Data Set has recorded more than 700 reported attacks against the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) and adjacent military units since 2015. The MNJTF consists of approximately 10,000 troops from Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, Niger, and Benin. Additional security forces from Lake Chad’s four riparian countries are also deployed throughout the MNJTF’s area of responsibility (AOR).

Despite this significant presence of military personnel, Boko Haram and ISWA have successfully attacked numerous fixed sites in the area. Sections have been targeted at checkpoints. Platoons have been targeted at outposts. Companies have been targeted at forward operating bases. Battalions have been targeted at sector headquarters. And dozens of supposedly secure sites, both small and large, have been overrun and their stores looted.

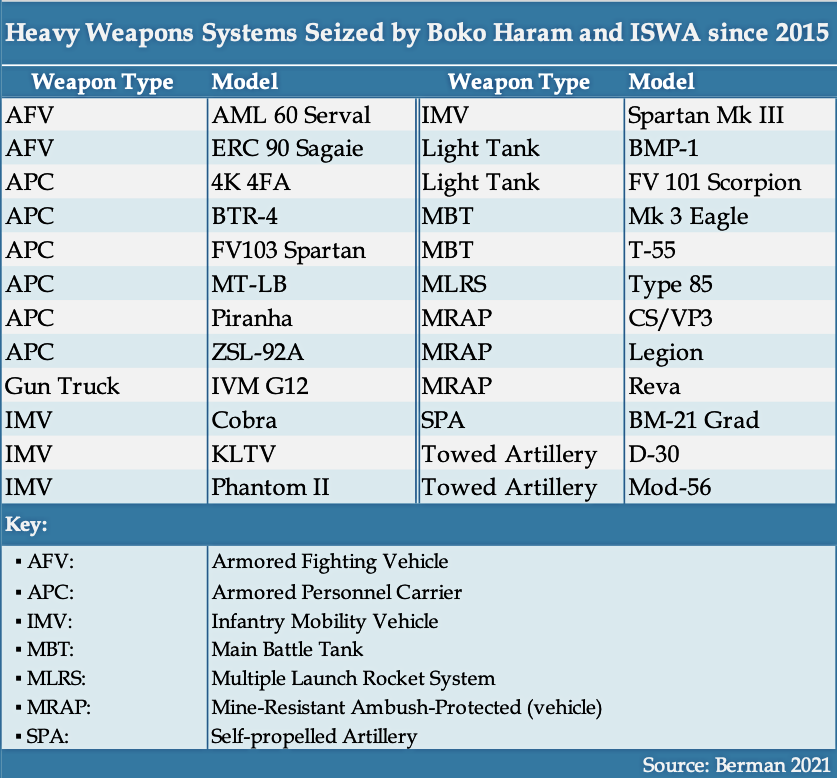

Such seizures of weapons systems and ammunition have allowed militants in the Lake Chad Basin to sustain their up-tempo operations. While these groups produce some handmade small arms and obtain a limited supply of lethal materiel on illicit markets, the insurgencies persist largely without external support. Boko Haram and ISWA, moreover, have not limited their seizures to small arms and light weapons. They have also seized artillery and numerous armored vehicles.

Details on the status, illicit procurement methods, and quantities of materiel holdings listed above are difficult to verify. Governments have reasons to deny and obfuscate losses, and armed groups have reasons to overstate their seizures. Data collected from open-source reporting suggest an incomplete snapshot that is likely only a fraction of actual losses.

Nonlethal materiel seized from Lake Chad Basin governments—such as uniforms, communications equipment, civilian vehicles—has also had serious ramifications for force protection. Militant groups have used civilian vehicles as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices. Additionally, they have used captured military vehicles and uniforms to camouflage their activities and enhance the effectiveness of their attacks by making their targets less vigilant.

Diversion of Arms and Ammunition from Other Peace Operations

Other peace operations and armed forces have experienced losses of lethal materiel to militant groups in circumstances similar to the MNJTF.

This problem is neither unique to Africa nor to African police- and troop-contributing countries (P/TCCs). For example, many European countries lost considerable materiel—including armored vehicles—in the UN missions in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Asian and South American P/TCCs have experienced losses of arms and ammunition in peace operations in the Caribbean, the Middle East, and Asia. But given the number of peace operations undertaken in Africa—and the large number of African countries participating in peace operations on the continent—losses of lethal materiel are a challenge that demands the attention of African policymakers and security professionals.

“Poor practices regarding weapons and ammunition management remain a serious concern across the continent.”

Loss of equipment does not suggest that a specific P/TCC lacks capacity or does not take its mission seriously. Peacekeeping is difficult and uniformed personnel deployed on these missions often face grave risks. Many African P/TCCs have earned reputations as effective peacekeepers and lost forces after coming under attack.

Nevertheless, poor practices regarding weapons and ammunition management remain a serious concern across the continent. Inoperable or insufficient equipment, endemic corruption, diminished morale, and lapses in battle readiness are often the primary cause of COE loss. Inadequate perimeter security practices as well as the lack of training, effective standard operating procedures, oversight mechanisms, and accountability standards further exacerbate the situation.

Reports from soldiers are rife with accounts of being insufficiently outfitted with body armor, ammunition, and other supplies. Corrupt procurement practices are also widespread and help explain why materiel is sometimes in short supply. Withholding wages and benefits, and longer-than-anticipated deployment lengths all have detrimental effects on morale and esprit de corps.

Current Conventions and Frameworks

Policymakers and practitioners within the arms control and peace operations communities have increasingly recognized the critical importance of mitigating COE loss.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), for example, have legally binding arms control conventions—with explicit references to peace operations—that entered into force in 2009 and 2017, respectively. Their 26 member states represent some of the most active P/TCCs in UN and African peace missions.

An African Union armored personnel carrier in Somalia.

(Photo: Enough/Laura Heaton)

The reporting requirements for ECOWAS and ECCAS provide control measures that should be aggressively employed. For example, the ECOWAS convention stipulates that its 15 members report all small arms and light weapons—along with their parts, accessories, and ammunition—that they contribute. Moreover, they are to report what they resupply, recover, or destroy during their deployment. Unfortunately, these procedures are not uniformly upheld. If this convention were rigorously adhered to, the secretariat’s accountability and inquiry process would be much more effective.

Small arms control frameworks of the Regional Centre on Small Arms in the Great Lakes Region, the Horn of Africa and Bordering States (RECSA) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) should be strengthened. They contain provisions for the disposal of confiscated or unlicensed firearms that, if more effectively employed, could help counter the recirculation of recovered lethal materiel in such missions. Their protocols, however, do not have explicit procedures for weapons and ammunition management in peace operations, leaving a blind spot.

Improving on Present Practice

Current practices have failed to stem the flow of lethal materiel to the armed groups that soldiers and peacekeepers confront on the battlefield. Without meaningful change, providing more weapons to states combatting nonstate armed groups may exacerbate conflict rather than resolve it. Degrading and preventing militant groups’ capacity to divert COE will require efforts and resources at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels.

On the ground, tactical adjustments for better force and equipment protection are essential to prevent battlefield losses. P/TCCs need to enhance perimeter security for their fixed sites. Soldiers need to be more aware and respond more ably to an enemy practiced in the art of deception (such as driving in captured army vehicles and wearing official uniforms). The design and implementation of berms and roadblocks can be done inexpensively, as can training of sentries responsible for distinguishing friend from foe.

“Tactical adjustments for better force and equipment protection are essential to prevent battlefield losses.”

In certain contested contexts, missions may benefit from limiting fixed defenses and static positions, which allow troop movements to be constantly monitored. Mobile units on near-constant patrol limit vulnerabilities associated with permanent basing strategies and can increase protection of civilians and peacekeeping forces by covering a greater area. Operating from a mobile posture does present logistical challenges for resupply. However, these can be overcome with greater investment in and an expanded role for military logistics units responsible for supply, transportation in and out the AOR, maintenance and repair, and their own self-sustainment capability.

Because illicit small arms and light weapons already circulate in the conflict-affected areas, mission mandates should include interventions aimed at severing illicit firearm sources through pre-deployment measures. These include:

- Mission-specific training in weapons and ammunitions management

- Marking and electronic record keeping of all weapons

- Effective management or destruction of all recovered small arms and light weapons

Similarly, African professional military education institutions have a role to play. Core curricula at military academies and specialized courses at command and staff colleges as well as war and defense colleges need to emphasize force protection and logistics across the continent.

P/TCCs can further improve on weapons and ammunition management within existing resources through adjustment to operational policies. Clamping down on corruption will enhance procurement plans without increasing defense budgets. Rotating uniformed personnel out of conflict zones within their expected periods of service will enhance morale. Greater transparency and fidelity to payment and benefit schemes will reduce troops’ proclivity to divert or abandon materiel.

AK-47 magazines collected in North Kivu, DRC.

(Photo: UN/Martine Perret)

Strategically, African and international organizations should take fuller advantage of existing arms control frameworks across the continent such as the ECOWAS and ECCAS conventions. Applying the control measures in these conventions more robustly and uniformly would provide enhanced oversight and professionalism. Moreover, doing so would support FC-G5S and MNJTF, which are new to peace operations and do not have their own arms control protocols.

The AU should also take advantage of its longstanding meetings with its eight Regional Economic Communities and the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), the Sub-regional Arms Control Mechanism (SARCOM), and RECSA to generate a better understanding of the scale and scope of materiel loss. This is something the AU’s “Silencing the Guns” initiative could lead, including assessing the challenge of securing heavy weapons systems.

Gaining better control of these lethal assets will simultaneously contribute to more effective security operations on the continent while diminishing a key resource sustaining militant groups.

Eric G. Berman is director of the Safeguarding Security Sector Stockpiles (S4) Initiative and a visiting scholar at Northwestern University’s Program of African Studies. He was formerly the director of the Small Arms Survey.

Additional Resources

- Eric G. Berman, “The Management of Lethal Materiel in Conflict Settings: existing challenges and opportunities for the European Peace Facility,” International Peace Information Service, September 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa Target Nigeria’s Highways,” Infographic, December 15, 2020.

- Daniel Eizenga, “Chad’s Escalating Fight against Boko Haram,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 20, 2020.

- Eric G. Berman “Beyond Blue Helmets: Promoting Weapons and Ammunition Management in Non-UN Peace Operations,” Report, Small Arms Survey, March 2019.

- Eric G. Berman, Mihaela Racovita, and Matt Schroeder, “Making a Tough Job More Difficult: Loss of Arms and Ammunition in Peace Operations,“ Report, Small Arms Survey, October 2017.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Peacekeeping Crucial for African Stability,” Spotlight, September 8, 2017.

- Daniel Hampton, “Creating Sustainable Peacekeeping Capability in Africa,” Africa Security Brief, No. 27, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 2014.

- Paul D. Williams, “Peace Operations in Africa: Lessons Learned Since 2000,” Africa Security Brief, No. 25, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2013.

- Helmoed Heitman, “Optimizing Africa’s Security Force Structures,” Africa Security Brief, No. 13, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2011.

More on: Conflict Prevention or Mitigation Peacekeeping Boko Haram Lake Chad Basin Nigeria Weapons Management